Regenerative in the Real World: The Kendeda building delivers.

Welcome to Atlanta, Georgia – the city in a forest – and now home to the Southeast’s first Living Building.

As of April 2021, Georgia Tech’s Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design became one of only twenty-eight buildings worldwide to be certified by the International Living Future Institute.

What that means is that rather than just aiming to be less harmful to the environment, the Kendeda Building is regenerative. In its normal operations, it gives back more to the environment than it takes, and it focuses on engaging with, and improving, the healthy and happiness of its occupants. It has been meticulously engineered to be able to produce more than double the amount of energy the building needs each year and collect and redirect fifteen times more water into the ground than it uses in daily operations.

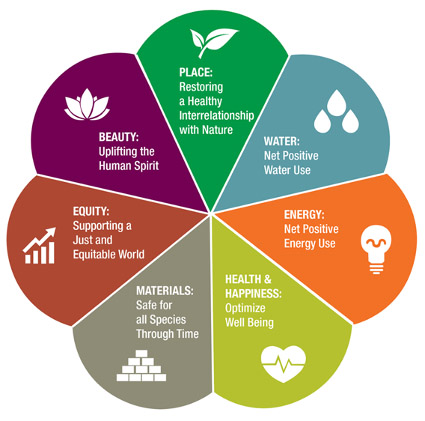

The Living Building Challenge is not just based on modeling or anticipated performance, but rather, actual performance. Each building must be able to verify its performance over the course of twelve consecutive months in each of the seven categories: water, energy, materials, equity, beauty, place, and health + happiness. These are referred to as the “petals” of a living building.

First announced in 2015 by The Kendeda Fund, an Atlanta-based philanthropic investment group, as a $25 million grant to Georgia Tech for the project’s design and construction, along with an additional $5 million for support activities and programming, construction was finally completed in late Summer 2019. The doors were opened in January 2020 – and then almost immediately closed due to the pandemic.

However, with the LBC certification received, and its doors re-opened for classes, the Kendeda Buildings champion-turned-director, Shan Arora, took some time to speak with The Net Positive about his day-to-day experience, some obstacles and lessons learned, and his new shift in focus towards the buildings true intended purpose – to educate and inspire the green building industry, whether property owners, contractors, engineers, or architects, as they seek to navigate environmental challenges in the southeast.

Shan Arora

Director of the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design at Georgia Institute of Technology

tNP: Shan, what does a living building mean to you?

SA: A Living Building, to me, represents a different way of interacting with, and a different way of relating to, both nature and ourselves. It shows us how it could be. Some may say should, but let’s not get overly preachy.

Regardless though, in showing that different way, it exposes some of the silliness of how it is that we currently construct our built environment, and what that does to nature through our relationship with nature, as well as our relationships with each other.

tNP: What do you mean by silliness?

SA: Well, one thing I’ve been asking visitors and web audiences lately is, “Why is it that we go to the bathroom in drinking water?”

The water we’re flushing down the toilet is the exact same water that comes from a tap, and it takes a lot of electricity to get water from the source to the tap, yet we’re just flushing that precious resource, and all that embodied energy, down the drain – sending it to treatment facilities that just require more power. Why aren’t we using graywater for toilets? Why can’t we just have a unified system of graywater pipes and use rainwater for toilets instead of clean, potable drinking water?

For me, it’s a rhetorical question – I know the answer.

It’s because polluting is cheap. The system is built that way.

It’s the same when it comes to incorporating salvaged material into buildings. It’s cheaper to just demolish or even blow-up buildings, send everything to the dump, and then buy new materials than it is to deconstruct, sort, and salvage what materials we can. We wouldn’t be sending so much stuff to the dump if it wasn’t so cheap.

One could argue that’s just the market price for the dump, but is it really? Does it really include the full life cycle cost of the dump, or do landfills just have a bit of that “well when the problem arises, it’s going to be a problem for the next generation, or the next century? If that cost is never born monetarily, it will eventually be born environmentally.

That’s what I mean by silliness.

tNP: So, after so much time getting the building open and operating, how does it feel to finally be spending all this time in a building with a net positive impact?

SA: You know, I do go home, sometimes. No, but in all seriousness, it feels great. It feels great knowing that when I go to the bathroom in this building, I’m not impacting the sewer – my bio-solids and liquids are not being treated as waste, but rather, they’re going to become fertilizer. And it’s awesome knowing that that I’m using 100% clean energy, and that it’s sending excess energy to neighboring buildings at Georgia Tech – All that’s great.

But my job, or rather, my mission, is to have these ideas scale across the Southeast, to where this is not just a one-off, but the first of many. Not necessarily the first of many ‘living buildings’, but the first of many buildings going beyond sustainability and really looking at how the buildings can contribute back to nature more than they take from nature.

In that regard, it can be a little frustrating because I feel that the speed at which things need to change – they’re just not changing fast enough. I know there’s a lot of moving parts, but things need to be changing faster than they are – or adapting faster than they are.

tNP: Has there been any noticeable impact on the industry since you opened or received the LBC certification?

SA: Let’s step back and talk about the green building industry as a whole. All of the different performance standards – you know, starting with LEED, the Earthcraft Standard we have here in the Southeast, Energy Star, and Living Building Challenge, especially with its strict, healthy materials requirement known as the ‘Red List’ – all of these things have impacted building and energy codes, and, really, have impacted the minimum acceptable level of performance. A house built today, if done right and done to code, is going to be much more energy efficient than a house built 20 or 30 years ago.

So, in that regard, it’s a bit of a continuum. I definitely think the Living Building Challenge, with that healthy material requirement, has had a tangible impact on the market. You see a lot more products with environmental declaration or cradle-to-cradle labels telling customers either what’s in their product, or that they are actively seeking to eliminate their products of these toxic materials. Again, not necessarily because of our building, but as part of that continuum that includes the Living Building Challenge.

Our particular building did have an impact on some of our subcontractors and change how they’ll do things going forward. That was part of the idea of constructing a fully certified Living Building in our region. You expose your subcontractors to new ways of doing things, healthier materials, and that’s hopefully going to carry forward in every other project they do.

tNP: What’s been the biggest obstacle? People?

SA: Well, from a performance perspective, the building is engineered to make it really hard for humans to derail the building’s performance. The goal of the Living Building Challenge is to be net positive at 105% over the course of a year. The Kendeda Building is net positive at 220% or more. It’s the same with both energy and water. It would most likely be a mechanical failure, and even then, we’ll find out about it pretty quickly.

But what we have been challenged with – which is more of a Georgia Tech requirement than a Living Building Challenge requirement – is material diversion. During the construction process, the building sent less waste to the landfill than it diverted, but during the construction process, we had complete control. Now that we’re in the normal operational process, we’ve got students and events, and it requires people to know what goes in the landfill, what goes in recycling, what goes in compost. We’ve got higher levels of contamination than we would like.

tNP: Have there been any significant lessons that you’ve learned since opening the building?

SA: One thing we’ve observed is that the students really enjoy being able to spend some time gardening, and I think there is an effort to expand urban gardening around the campus as a health and wellness initiative. You know, when you’re gardening, you have to put your phone down – you’ve got to disconnect for a couple hours. Some students really look forward to that, and Georgia Tech wants to encourage that.

The other big thing is incorporating healthier materials. Georgia Tech is developing a new campus master plan, and their supposed to be incorporating a healthy materials guideline for new buildings. We’ll see what other lessons and guidelines they adopt from the Kendeda Building whenever they release it.

tNP: How do you share these strategies, functions and lessons with the people using the building on a daily basis?

SA: Well, the workers, the staff – we’re all on board. We know that. But how do we convey it to the students?

Well, some students are just going to be oblivious. Others know the building is special, and they’ve got some idea what’s happening. But then there’s a smaller subsection, and they’re, really, much more deeply involved in what we do here. Of course, we’ve got active social media (@Kendeda) across almost all platforms, and we try to use that to share what’s happening.

Right now, for example, we have America Recycles Day, so we’ve got a station outside where people can bring a long list of hard-to-recycle materials, like e-waste. And to shed some light on fast fashion – and its impact – we’ve had a revolving closet for a month now. People can bring clothes and take clothes freely, with the idea being that instead of going out and buying new clothes, come see what’s here, wear it for a semester, and bring it back after you’re bored of it. We’re also accepting clothing for recycling that can’t be reused, instead of – you know – it being thrown in a dumpster.

Obviously, I speak to a lot of students, too. We give a lot of student tours, and not just to students from Georgia Tech. We’ve given tours to maybe 20,000 people in the last three or four years, even before the building was constructed.

We do what we can.

tNP: What’s been your greatest experience in the building so far?

SA: I’ll tell you – it’s getting the opportunity to speak to the right people. We’ve spoken with everyone that has come through those doors – students, architects, builders – everyone. We try to follow up with them as best as we can, influence them, but what those individuals do with the knowledge we share – that they gain – is up to them.

Every single one of them is now a seed, and where that seed germinates and what that seed becomes, I don’t know. Not every seed germinates. Not every seed becomes a plant. But everyone who walks out of this building does become a seed, and that’s exciting.

tNP: What would you say is on your biggest fear for the building, and what would you say is on your wishlist?

SA: I mean, my biggest fear and my wishlist are essentially the same. My biggest fear, without a doubt, is that the building remains the most sustainable building in the Southeast for a decade. It needs to be knocked off its perch – as soon as possible – and it needs to be relevant more as a historical marker or footnote as opposed to the apex. My biggest fear is that, eight years from now, we’re still talking about how revolutionary this is.

My goal, from the beginning, was that five years after opening, this building would cease to be the most sustainable building – the building that everyone’s talking about in the southeast, if not the world – and we’re two years into the opening of the building. So, my wishlist is that, within three years, this thing – this building – is no longer the “it” building.

And then that next building is the “it” building for maybe two years, and then the building after that is the “it” building for one year, and then there’s so many that it’s not a global news story, or even a national story anymore. It’s just a story for the state, and then the locality.

It’s like with LEED Platinum buildings – you’re not seeing news reports for every LEED Platinum building that’s being built. But, if you go to our homepage, under resources there’s a link for media, and you’re going to see – just this year alone – 30 stories about the building.

I mean, I want these buildings to keep generating news stories, but at a local scale, not global, because regenerative buildings have become normal.

___

Check out the Living Building Chronicle to read more about the evolution of this project, and if you’re in the area, schedule a tour to go see it in person, or via webcam.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Living Building Challenge, you can click the link to jump to the LBC basics, or head to the ILFI homepage to check out more of their programs and initiatives.